Photosynthesis is the basis for all plant life, yet most gardening guides only mention it in passing, if at all. If you’re unfamiliar, photosynthesis is the process plants (as well as some bacteria, algae, prokaryotes, and some protist) use to turn energy from sunlight, in combination with water, and CO2 into essential sugars (and as a byproduct we get oxygen). These sugars (carbohydrates) are essential for the plants survival, as they provide fuel for the cells (energy), in addition to providing much needed carbon (This is what we are talking about when you hear carbon fixation mentioned). It’s worth mentioning, biosynthesis of cannabinoids and related compounds are incredibly energy intensive on a molecular level. The amount of cellular energy required to biosynthesize terpenoid molecules has been calculated to be up to three times greater than that required to synthesize an equivalent weight of sugars(1). If this all seems a bit boring, don’t worry! This topic is not without its rewards!

Haven’t you ever wondered why some plants do better under intense light than others? Why badly cured weed is so harsh? Why LED (as well as some other types of lights) seem to bring out interesting colors in the flowers, and leaves in some strains? Or why we choose the light cycles that we choose? Luckily for us, some of these things are outright explained by the biochemistry, while others are hinted at, inviting us to explore further and document the results ourselves.

(1) – Handbook of Cannabis, Oxford Press, Pg. 80

Table of Contents

Intro to Photosynthesis

Understanding Photosynthetic Pigments

Intro to the Biochemistry of Photosynthesis

The Light Dependent Reactions

The Calvin Cycle

Photorespiration in C3 Plants

Intro to Photosynthesis

Photosynthesis takes place inside an organelle, called chloroplast. Chloroplast is found in any green plant tissue, like stems, and buds, though it is most abundant in the leaves. On a cellular level, chloroplast is contained within the mesophyll cell, the tissue in the interior of a leaf. Generally a mesophyll cell will contain about 30-40 chloroplast, each only about 2-3 µm by 4-7 µm. Carbon Dioxide (CO2) enters the leaf via small pores on the surface of the leaf called the stomata (or stoma when you are referring to a single pore) and diffuse into the mesophyll layer while oxygen (O2) diffuses out.

A cross section of the organelle chloroplast – Photo courtesy of Georgia State University

Inside the chloroplast (passed its two membranes) is the fluid filled stroma. Floating around this fluid are disc-like structures called thylakoids, that are arranged into stacks like pancakes, which are collectively referred to as grana. Within the membranes of the thylakoid is where we find chlorophyll, the photosynthetic pigment that gives leaves their characteristic green color, and the vary same pigment that drives photosynthesis. Inside the thylakoid, passed its membranes, is the thylakoid space, also called the lumen. While you don’t really need to memorise everything just mentioned, it’s helpful to look back at this as we go through the biochemistry so you understand where it is happening.

Understanding Photosynthetic Pigments

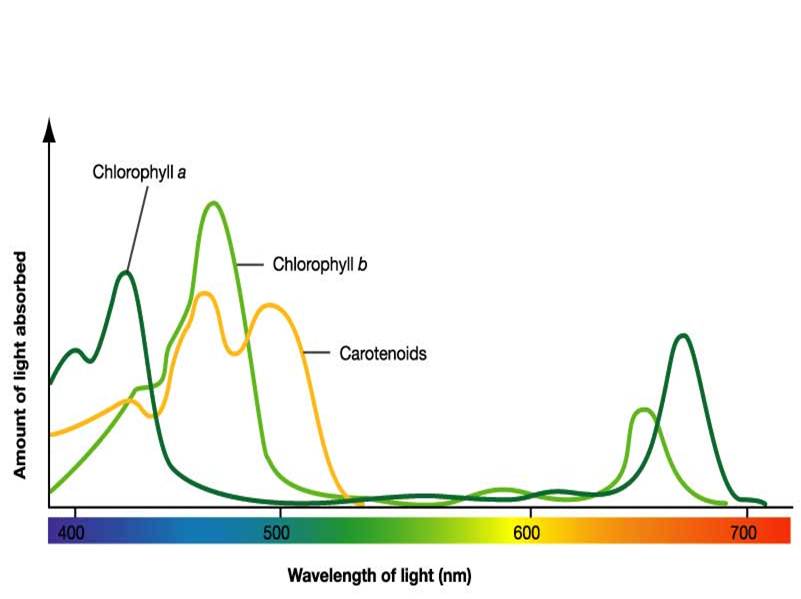

Above I mentioned where we find chlorophyll, and that it’s a photosynthetic pigment, but you may be wondering what that really means. When light, in the form of photons, interacts with matter it can be reflected, transmitted, or absorbed. When a substance absorbs visible light, its called a pigment. Chlorophyll actually is a class of pigments, of which the two most abundant forms are Chlorophyll A, which drives the light-dependant reactions, and Chlorophyll B, an accessory pigment. (Chlorophyll C and Chlorophyll D also exist). In addition to Chlorophyll B, you have other accessory pigments, such as carotenoids, and anthocyanin (there’s actually a few others like anthoxanthin, however I can’t find anything suggesting they occur in cannabis.).

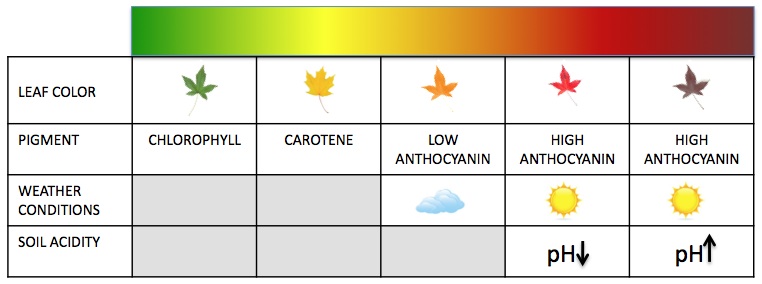

When we look at a leaf, and it appears green it is because this spectrum is reflected by pigment it contained. That might lead you to ask, what about when leaves or even flower (bud) is purple? This is simply the result of high concentrations anthocyanin, the same water soluble accessory pigment found in purple cabbage. You may have done an experiment in high school with purple cabbage to show pH. which happened because anthocyanin is both water soluble, as well as incredibly pH sensitive. We see this as purple as it is the spectrum of light that was reflected, and not absorbed. While anthocyanin appears as purples, reds, and pinks, conversely carotenoids absorbs violet to blue-green light and instead reflects (and thus appears to us as) shades of yellow and orange. Think about the color change we see in leaves from spring to fall on the trees all around us. In fall chlorophyll undergoes degradation, eventually to the point of not being expressed. The residual pigments, carotenoids, anthocyanin, etc, are what’s left, and thus what we see light reflected from.

Leaf Color Chart – Photo Courtesy of Wikimedia

Having mentioned Chlorophyll A, I’d be remiss in not sharing why knowledge of it is helpful to understanding curing. Ever smoked bud that’s been cured too fast, or worse yet not cured whatsoever? It’s incredibly harsh, and taste of grass clippings. Chlorophyll A, the most common form of chlorophyll will degrade into Chlorophyllide, when reacted upon by the enzyme Chlorophyllase. When we correctly cure our flower, we give time for chlorophyll A to be degraded into Chlorophyllide, among other process (1) (such as the utilization of residual nitrogen, as well as the break down / utilization of some starches, carbohydrates, and proteins.) (2)

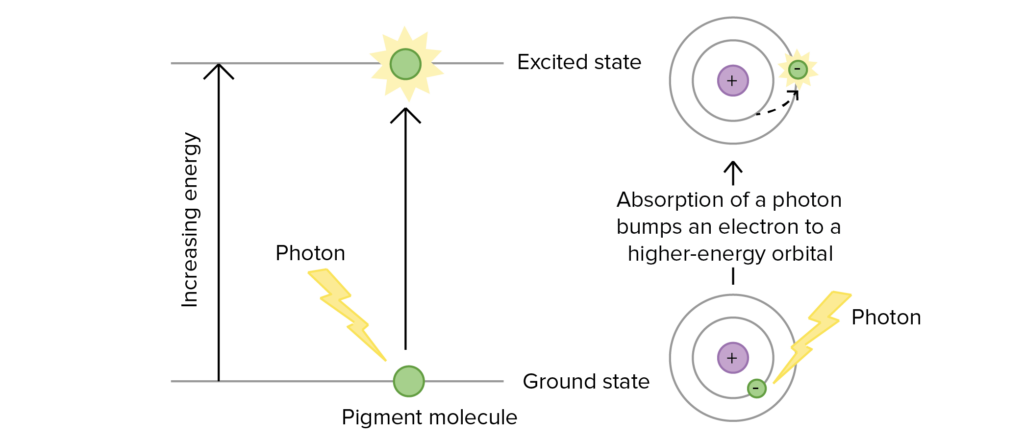

When light hits the mass of pigments found in photosystem, energy is transferred from molecule to molecule (via Förster resonance energy transfer, all happening within about a millionth of a second) until it reaches the reaction center. Once at the reaction center, the energy from the photon excites an electron of said reaction center pigment to an elevated orbital, increasing its potential energy as well as causing the excited pigment to be energetically unstable. When the pigment’s electrons are in their normal orbital, the pigment is said to be in its ground state, where it is stable.

Excitation of an electron during photosynthesis – Photo courtesy of Mitch Singer at OpenStax

Absorbance of energy at the reaction center requires a certain wavelength of light in order to bring the pigment from its ground state to an excited state. The only wavelength that will react with the pigment is one whose energy is equal to the difference in energy from ground state to the excited energy state. This is why each pigment has a unique absorption spectrum.

Absorbance spectrum of the three most common pigments – Photo Courtesy of Wikimedia

What’s really interesting about accessory pigments is that not only do they broaden the spectrum of light that is absorbed for photosynthesis, in many cases they also act as photoprotection. While plants require light to live, certain spectrums as well as to high of intensity light can be damaging to the plant. Most accessory pigments are also known to be photoprotective pigments, meaning they can absorb and dissipate the excessive light energy that would otherwise damage chlorophyll, or even form dangerous reactive oxidative molecules otherwise. When I first mention photosynthesis, I mentioned how some strains seem to respond to high intensity LED by becoming more colorful. By now, I hope it is apparent that this is because of heightened production of accessory pigments. While the capacity for a strain to produce accessory pigments is something that’s really not been studied to the depths it deserves, it does seem of interest. From what we understand now, it does seem it’s this capacity that leads to a strain being more adaptable to various lighting technology or intense lighting conditions.

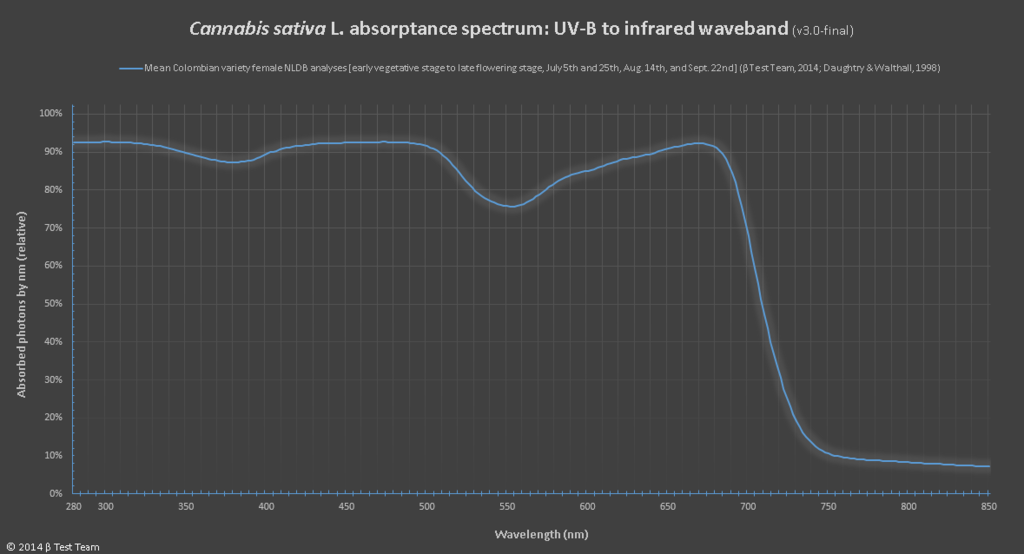

The absorbance of UV-B light in cannabis sativa

For those of you that have found everything so far fascinating, you might be curious to know that the device used to find out what light spectrums a pigment will absorb or reflect is a device known as a spectrophotometer. To use one you would prepare a solution of pigment in question, which would then have beams of various wavelengths of light directed through the solution. This allows you to measure the fraction of light transmitted through the pigment for each wavelength. From there you can calculate the absorption spectrum via a graph where the pigment’s light absorption versus the wavelength are plotted against each other. With that data you can create the more common action spectrum, by lighting up the chloroplast with specific wavelengths of light, while measuring against a measure of photosynthetic activity, CO2 consumption or O2 release for example.

Intro to the Biochemistry of Photosynthesis

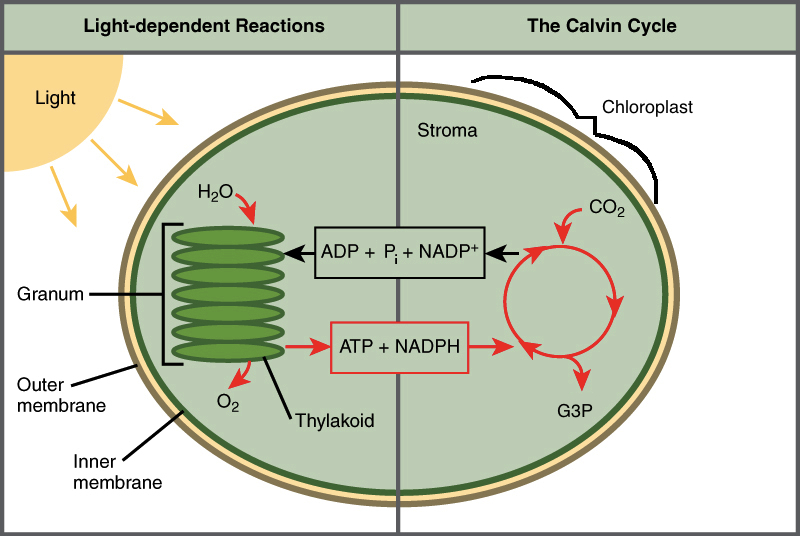

The Cycles of Photosynthesis – Image courtesy of Khan Academy

The biochemistry of photosynthesis is broken down into two cycles. The Light-Dependent Reactions (the Photo part of photosynthesis), takes place in the thylakoid membrane. It’s during these reactions where photons interact with chlorophyll, allowing their energy to be converted into chemical energy for later, in the forms of ATP, and NADPH. During this process, Oxygen (O2) is released into the atmosphere as a leftover byproduct after extracting an electron from water (H2O).

The Calvin Cycle aka the Light-Independent Reactions (the Synthesis part of photosynthesis) takes place in the stroma. These reactions can be broken down into three phases, fixation, reduction, and regeneration. It’s during these phases that ATP, and NADPH produced during the light-dependant reactions, are used to fix CO2 molecules into three-carbon sugars called G3P (Also called PGAL, or 3-Phosphoglyceraldehyde). Later, this G3P can join up and create glucose.

It’s worth noting that both of these cycle are happening simultaneously.

Light Dependent Reactions

Light (UV Photons) + H2O —> ATP + NADPH (+O2)

First, as you may have guessed, this cycle gets its name because it requires energy in the form of light (UV Photons to be specific) in order to begin. The “equation” above is a deceptively basic way of looking at what happens during the Light Dependent Cycle. These reactions are further broken down into the two main phases, Photosystem II and Photosystem I. It’s worth noting that Photosystem II got its name simply by being discovered after Photosystem I, although the reactions start at PSII and then move to PSI. This can be a bit confusing at first, but shouldn’t take to long to get used too.

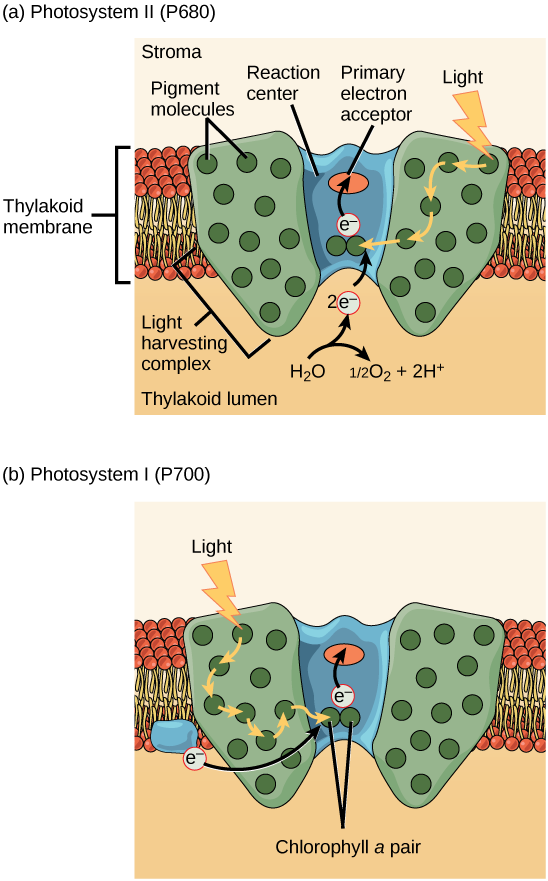

Photosystem II top – Photosystem I bottom – Photo courtesy of Mitch Singer at OpenStax

A photosystem is a multiprotein complex comprised of a reaction center surrounded by several light harvesting complex. The reaction center, in botanical terms, is a part of the plant that can be electronically excited, and is able to donate electrons upon excitation. From the cellular biology perspective, a reaction center is a group of special proteins that hold a unique pair of chlorophyll a molecules. This pair of chlorophyll molecules can undergo oxidation when they are excited, meaning once excited they can donate an electron to a primary electron acceptor.

Surrounding the reaction center we find various pigments (chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, carotenoids, anthocyanin, etc) bound to proteins. This combination of protein / pigment compounds are referred to as antenna proteins, and the collection of these antenna proteins is the light-harvesting complex. In the case of Photosystem II, that reaction center is called P680, whereas in Photosystem I the reaction center is P700. P stands for pigment, 680/700 refers to the nanometer of wavelength of light that they are excited by. When a reaction centers donates an electron to the corresponding electron acceptor, they’ve begun the photosynthetic electron transport chain. Now that we’ve discussed the basics of photosystems we’re finally ready to cover photosynthesis step by step.

The interior of the thylakoid lumen aka thylakoid space – Photo Courtesy of Wikimedia

Science Corner

You may remember some variation of these acronyms from high school:

LEO GER

Lose Electrons we have Oxidation, Gain Electrons we have Reduction

OIL RIG

Oxidation Is Losing, Reduction Is Gaining

What this means to us is that when we have a molecule that gives up its electrons easily, it’s a very good reducing agent. Conversely, if we say something is good oxidizer it just means that it wants to take up an electron/electrons. If a molecule gives up an electron its charge goes up, whereas the molecule acting as the electron acceptor is gaining an electron and so it is going to go down in charge. If you’ve ever read about separation of charge, this is what you’d be keeping in mind. While you don’t have to understand this, try and keep it in mind as you continue reading, as it will be of use.

Photosystem II

Light, in the form of photons, interacts with the photosynthetic pigments that make up the light-harvesting complex within photosystem II. The spectrum of light that is reflected, is the the wavelength we see when we look at the plant tissue. Energy (but not the photons themselves) from the spectrum that was absorbed however passes from pigment to pigment until it reaches the P680 reaction center, where it excites it. (When P680 has a electron excited we write it as P680*. P680* is a strong reducing agent.). P680* then donates these excited electrons, one at a time, to the primary electron acceptor, pheophytin. This step is the beginning of the photosynthetic electron transport chain. Now that P680 has donated an electron, it has an electron hole it wants to have filled. (When P680 becomes oxidized, and thus needs an electron, we write it as P680+). P680+ is the strongest known biological oxidizing agent, with an estimated redox potential of ~1.3V, allowing it to syphon an electron from H20, leaving O2 as the byproduct.

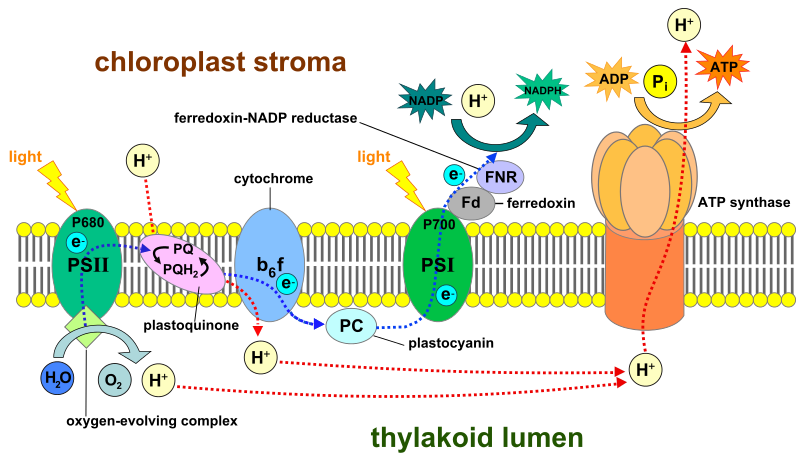

Photosynthetic Electron Transport Chain

Pheophytin passes the excited electron onto plastoquinone, who then passes the electron onto the cytochrome complex. The excited electron, while traveling along the electron transport chain, is losing bits of energy at each step, with some of that energy being used to drive a molecular Hydrogen (H+) pump in the B6F cytochrome complex. This pump moves H+ from the stroma into the thylakoid interior. This begins to build a H+ concentration gradient. In addition, the H+ that was a result of splitting water to return an electron to P680 is also stored here, further increasing the gradient. This gradient is then used to fuel the production of ATP by ATP synthase. It does this because H+ wants to go down the concentration gradient, and as it does so through the ATP synthase pathway within the cytochrome complex, which essentially turns a cellular motor that can jam the phosphate group onto ADP to produce ATP, a process called chemiosmosis. The electron is now transferred from the cytochrome complex to plastocyanin, which delivers it to Photosystem I. Traveling the electron transport chain has caused the electron to have lost significant enough energy that it must once again become excited by a photon, this time upon arrival at the PSI reaction center.

Photosystem I

Once light has excited PSI, it becomes an excellent electron donor, though this time sending the electron on a much shorter ride upon the electron transport chain. The electron moves from PSI to the protein Ferredoxin, and from there to an enzyme called NADP+ reductase. This enzyme will transfer electrons to NADP+, creating NADPH. NADPH, along with the ATP generated via ATP Synthase we talked about earlier, are now available to the Calvin Cycle, thus completing the Light-Dependant Reactions.

The Calvin Cycle

ATP + NADPH + CO2 -> Calvin Cycle* -> PGAL aka G3P aka Phosphoglyceraldehyde

*Under ideal conditions where photorespiration is not taking place

These reactions have been renamed over the last few decades, and for good reason. Originally coined ‘dark reactions’, this name has been completely dropped in modern biology, as it incorrectly implied the reactions occur at night, or in the dark. Instead, scientist and teachers alike now refer to this as either the light-independent reactions or more commonly, The Calvin Cycle ( or sometimes the Calvin-Benson-Bassham cycle when making an effort to include all the scientist involved in its discovery).

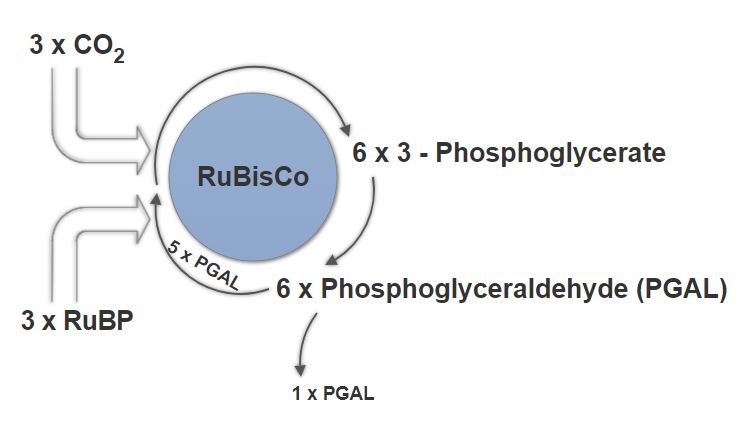

The Calvin Cycle is mostly driven by the enzyme RuBisCo, aka ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase.

Fixation

Within the stroma, where carbon fixation begins we quite suitably find CO2. CO2 filters in via stomata, diffusing in the mesophyll cell, eventually into the stroma. Alongside this CO2, you’d also find the aforementioned enzyme, RuBisCo, as well as three molecules of ribulose biphosphate (RuBP). RuBP is a five carbon molecule, with two phosphate groups.

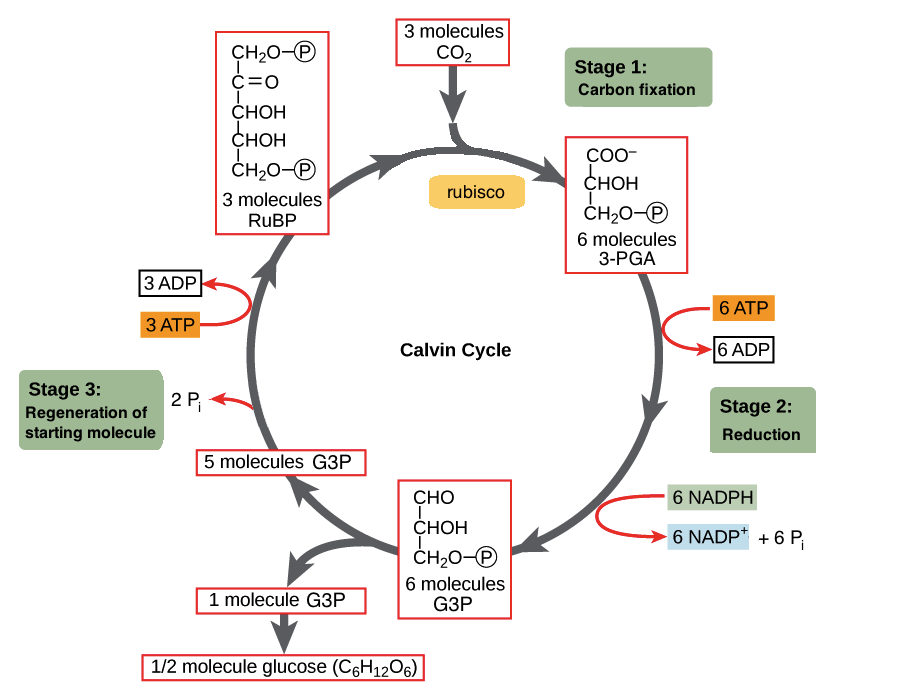

The Calvin Cycle – Photo courtesy of OpenStax College

RuBisCO acts as a catalyst for the reaction between CO2 and RuBP. For every molecule of CO2 that reacts with one RuBP, two molecules of another compound (3-PGA) form. PGA has three carbons and one phosphate. Every time around the cycle involves only a single molecule of RuBP, and one of CO2 and with those forms two molecules of 3-PGA. The number of carbon atoms remains the same, as the atoms move to form new bonds during the reactions (3 atoms from 3CO2 + 15 atoms from 3RuBP = 18 atoms in 3 atoms of 3-PGA). This process is called carbon fixation, because CO2 is “fixed” from an inorganic form into organic molecules.

Reduction

Now using a few of those ATP and NADPH generated during the Light-Independent Cycle, we can convert the six molecules of 3-Phosphoglycerate into six molecules of PGAL, as shown below. If you remember from us covering it above, anytime a compound gains electrons we call it a reduction, and thus the name for this phase. Our ATP, energy now spent (via loss of its terminal phosphate atom) is now ADP. Similarly, the NADPH has now lost its energy as well as its hydrogen atom, causing it revert to NADP+. These ADP and NADP+ quickly rejoin the light-dependant system to be reused and reenergized.

The Calvin Cycle under ideal conditions in a C3 plant

Regeneration

As you can see above, a single molecule of PGAL leaves the Calvin Cycle, and it does so through the cytoplasm, allowing it to be turning into other useful compounds. Since PGAL has three carbon atoms, it takes three “cycles” of the Calvin cycle to fix enough net carbon to export one molecule of PGAL. However, each turn makes two molecules of PGAL, thus three turns make six PGALs. One is exported while the remaining five molecules remain in the cycle and are used to regenerate RuBP, enabling the plant to prepare for more CO2 to be fixed. Three more molecules of ATP are used in these regeneration reactions.

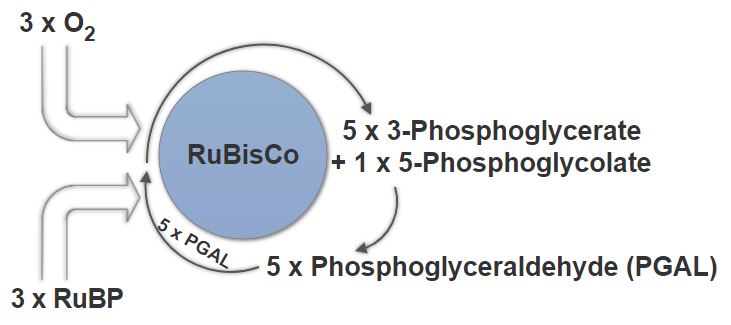

Photorespiration

Photorespiration in a C3 Plant

In C3 plants, which Cannabis Sativa(1) is, photorespiration is an issue. Rubisco, which drives the Calvin reactions, cannot differentiate between CO2 and O2. Under stressful conditions, such as an excessively hot, or dry environment Rubisco will perform its reaction with oxygen instead, creating 2-Phosphoglycolate, which is ultimately useless for the plant. To try and salvage this into something usable the plant must undergo photorespiration, an incredibly wasteful pathway.

2-Phosphoglycolate will have to react with 2-Phosphoglycolate Phosphatase to give glycolate. Glycolate will then have to react with glycolate oxidase to give glyoxylate, which will then have to react with glutamate glyoxylate transaminase to get glycine. Glycine will react with glycine decarboxylase complex to give serine. Serine will then react with serine-glyoxylate-transaminase to give pyruvate, which then reacts with pyruvate reductase to give glyceride. Lastly, this glyceride must react with glycerate kinase to give a single molecule of 3-phosphoglycerate, which will only allow cycle to begin again.

Just to deal with 1 molecule of 2-phosphoglycolate the cell must waste 2 NADH and 2 ATP. Now consider the number of sites that would simultaneously going through this waste reaction.

(1) – The Biotechnology of Cannabis Sativa, 2nd Ed.